Sho (書) is both the practice of writing by hand and the appreciation of handwritten texts. It is perfectly possible to appreciate calligraphy without actually practicing it, just as it is possible to be a music lover without being able to play an instrument. However, through the practice of calligraphy, our ability to appreciate the work of others increases greatly.

For those who are serious about developing their calligraphic skill, the study of classics is essential. First and foremost, it broadens and deepens our powers of ingenuity: studying classics enables us to encounter hitherto unknown techniques, forms of kanji, line shapes and weightings, approaches to composition, and so on. With practice, these become internalized and available for us to use when we write our own original compositions.

Our eyes and arms are not the only beneficiaries of this kind of practice. To reproduce the shapes we see when presented with a classic, we must deduce the way in which they were written: the speed, pressure, and angle of the brush, the fluidity in changes of direction, and how the lines connect. This gives us an insight into the methods used by the calligrapher whose work we are studying.

As mentioned above, another benefit of studying classics is that it allows us to gain a deeper appreciation of the work of other calligraphers. Pieces which at first glance appear to be unrefined or possibly even childlike turn out to be masterpieces of originality demanding a high degree of skill when we attempt to replicate them.

This is something that I have experienced on several occasions, most notably with the work of the Song-dynasty calligrapher Huang Tingjian (黄庭堅). At first glance, I was less than impressed: the characters appeared awkward and irregularly distributed, as though hurriedly jotted down with no aesthetic sense.

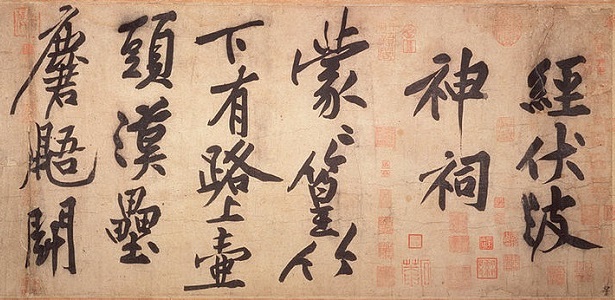

Part of the poem in running script by Huang Tingjian (黄庭堅).

At the time, I was submitting my work every month to the Kyūryū Calligraphy Society, one or two pieces of which would be studies of classics selected by the head of the society. One month, the selected classic was Huang Tingjian’s famous poem written in running script (行書 伏波神祠詩巻, Japanese: gyōsho-jōha-shinshi-shikan). It only took a few sheets of practice for my opinion about this calligrapher to change completely. Now, Huang Tingjian is one of my favorite calligraphers, and I jump at the chance to see his original pieces in museums.

A further benefit of the study of classics is that through them we learn about the calligraphers themselves, the periods in which they lived, and the materials they used. Reading the commentaries on classics written by experts can reveal aspects that would otherwise not be obvious. For example, the Yuan-dynasty calligrapher Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫) was admired by the Mongol emperor of China because he wrote in a very conservative style. The foreign emperor wanted to show the Han people that he respected their history and cultural traditions and thereby gain their support. As a result of the emperor’s favor, Zhao Mengfu’s calligraphy undoubtedly gained greater status than it would otherwise have done.

Part of Epitaph for Chou E in regular script (楷書仇鍔墓誌銘巻, Japanese: kaisho-kyūgaku-boshimei-kan) by Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫).

The study of classics in calligraphy is known as rinsho (臨, rin: to look out on, to face; 書, sho: writing) in Japanese. Rinsho can be subdivided into three distinct types.

Keirin (形臨)

(形, kei: shape, form; 臨, rin: to look out on, to face)

This is the most basic form of rinsho and an essential stepping-stone to the other forms. The goal of keirin is to replicate the shapes of the lines and the characters in the original. In keirin, one keeps a copy of the original in view whilst writing.

Irin (意臨)

(意, i: idea, mind; 臨, rin: to look out on, to face)

Having practiced the shapes in the original, move on to trying to write it with the intent and style of the original calligrapher: this is irin.

To do this, it is essential to have already practiced at least a significant portion (if not all) of the original and observed the common forms and techniques as well as noting the degree of variation in the piece. At this stage, it is still a good idea to have a copy of the original to hand, but rather than looking at the shapes of individual lines and characters, look to see if the overall impression of your writing is true to the spirit of the original.

Hairin (背臨)

(背, hai: back (part of body), height; 臨, rin: to look out on, to face)

The most advanced stage of rinsho is hairin. At this point, you no longer look at a copy of the original, but try instead to write it from memory. To do this, you can either use the printed form of the characters (活字, katsuji) in the original or write other characters—maybe a poem or a saying.

Hairin is the basis of original composition (創作, sōsaku). After practicing a piece or several pieces by a single calligrapher, you can then try using their techniques to write your own pieces. Through extensive rinsho, the techniques of multiple calligraphers can be acquired and combined into your own original style; the development of an original style is one of the goals of calligraphy.

Different teachers and schools of calligraphy place different levels of emphasis on rinsho. Here at Yōsetsu, rinsho is a fundamental component of practice. Moreover, we believe that to truly get the essence of a piece of calligraphy, it must be thoroughly practiced. For example, I devoted four years to the study of zhang meng long bei (JP: 張猛龍碑, RO: Chōmōryōhi), one of the classics of Northern Wei dynasty kaisho. Each week, I would write 24 characters and only move on to the next 24 with the blessing of my teacher.

Of course, the benefits of rinsho can be obtained without going to such extremes. Some people prefer to “chop and change” regularly, maybe studying a classic for a month or just a week at a time. At the beginning of your study, it is a good idea to practice a range of different classics to allow you to discover the styles and calligraphers that most appeal to you. We hope that the samples of rinsho on this site will help you on your way.

One final but important note: Rinsho should not become mindless practice for its own sake. It is, as mentioned above, an important stepping stone to original composition. However, it is only a stepping stone. When choosing which classics to study, do it on the basis of selecting the styles that you would most like to incorporate into your own original works.