Chinese characters (known as kanji in Japanese) have been written for more than three thousand years. Their shapes and the ways in which they are written have evolved gradually. This evolution has been due to technological changes (such as the invention of paper), social changes (such as the unification of China under the first emperor of the Qin dynasty), and the experimentation of individual calligraphers.

As such, the development of different styles has mostly been a fluid process, and it is difficult to pin down precisely when a particular style first emerged. However, scholars of calligraphy generally identify the following principal styles.

Seal script or tensho (篆書)

Seal script gets its name from the fact that this style has been the most common choice for the letters on the marble, wooden, or plastic seals which are used for signing documents in Japan and China, similar to signet rings in the West. Unlike signet rings, which have been replaced by signatures, seals are still in common use in Japan.

Modern-day Japanese seals or hanko (はんこ, hanko).

Seal script is further divided into sub-styles depending on the materials in which examples of this form of writing have been preserved.

(a) Kōkotsubun (甲骨文)

The oldest surviving examples of kanji were carved into turtle shells or animal bones. The writing on such relics is called kōkotsubun (甲, kō: turtle shell; 骨, kotsu: bone; 文, bun: text). The inscriptions were used for divination purposes, and as a result, they are sometimes referred to as “oracle bones” in English. Because they were carved into hard materials using sharp tools, the kanji are very angular. Many of the kanji which were in use at this time depict the things that they represent. This style dates back to approximately 1200 BCE.

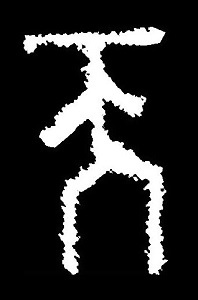

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the kōkotsubun sub-style.

(b) Kinbun (金文)

As techniques for casting bronze developed, people learned that if they wrote on leather with a brush, cut out the shapes of the kanji with a knife, and pushed the leather into the wet clay of the mould for a bronze ceremonial vessel, the deeds of their rulers could be beautifully preserved in metal. This style is called kinbun (金, kin: metal; 文, bun: text), and it dates from approximately 1100 BCE. Because of the softer materials, kanji in the kinbun style are much more rounded than those in the kōkotsubun style. However, the kanji used in such inscriptions remained highly pictographic.

One of the most famous Chinese bronze ceremonial vessels, the Da Yu ding (大盂鼎, daiutei). Note that the text is on the inside of the vessel.

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the kinbun sub-style.

Clerical script or reisho (隷書)

Because of it was so useful, writing started to spread in ancient China. One of the cheapest and most readily available materials to write on was wood. The grain of the wood caused the shapes of kanji to change: rounded forms became square. Writing with a brush (as opposed to carving) meant that it was a simple matter to produce varying line thicknesses. The result was reisho (隷, rei: slave; 書, sho: writing), which is known as clerical script in English because many of the earliest surviving examples of the use of this style are records taken for taxation and other administrative purposes. The style dates from about 250 BCE.

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the reisho style.

Cursive script or sōsho (草書)

As paper became more affordable and literacy increased, cursive forms of kanji began to appear. The older, slower styles of writing would not have been practical for writing drafts of letters or noting down the spontaneous poetry of the literati at their drinking parties. With the advent of cursive forms, we see the increasing presence of expression in writing; not just technique. The sōsho (草, sō: grass; 書, sho: writing) style dates from around 150 CE.

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the sōsho style.

Running script or gyōsho (行書)

Gyōsho is another cursive form. Unlike lines in sōsho, which are generally written with a 1-2 rhythm (beginning and end), lines in gyōsho are generally written with a 1-2-3 rhythm (beginning, middle, and end). Moreover, the shapes are closer to their reisho predecessors. Gyōsho permits expression through its fluidity, whilst retaining the intricate structures of individual kanji. The gyōsho (行, gyō: go, carry out, line; 書, sho: writing) style dates from around 250 CE.

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the gyōsho style.

Regular script or kaisho (楷書)

By using thicker lines on the right side of kanji and tilting horizontal lines toward a vanishing point on the left, calligraphers found they could make characters seem three-dimensional. Viewers get the impression that they are looking up at some majestic structure. This was a fitting choice for the inscriptions on the Buddhist statues and temples which were being erected with fervour at the time this style appeared, around 450 CE. Its legibility and popularity account for the use of kaisho (楷, kai: correctness; 書, sho: writing) as the “regular” style which children in both China and Japan learn at school.

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the kaisho style.

Japanese phonetic characters or hiragana (ひらがな)

Around the 5th century CE, kanji were imported into Japan and gradually retrofitted to the existing spoken language. Fundamental differences in grammar between Chinese and Japanese meant that the Japanese language also needed a phonetic syllabary (characters with sounds but no meaning) in order to be written down. For example, the tense of a verb is specified in Japanese by the sound of its ending, e.g., taberu (食べる) means “eat” and tabeta (食べた) means “ate.” In Chinese, the tense of a verb is usually not specified; it is understood from the context in which the verb is used.

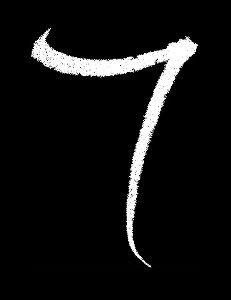

The Japanese phonetic syllabary known as hiragana was created by further smoothing the cursive sōsho forms of kanji with similar sounds to the ones required. For example, a highly cursive form of the kanji 天 (ten: heaven) was used to represent the sound te (て). This style was used from around 1000 CE by aristocrats to write poetry and love letters. It possesses that typical Japanese aesthetic of subtle and poignant movement against a backdrop of serenity.

The character 天 (ten: heaven) in the hiragana style.