The conference’s opening address.

Theme

“Inscriptions can open up a world extending far beyond chisel marks on the stone surface. In eight roundtables, we propose to explore the rich cultural history of epigraphy in East Asia. By striding out its multiple dimensions of time and space, both physical and imaginary, scholars from the sinographic sphere with diverse disciplinary backgrounds will attempt to chart together the Epiverse. The experimental format of this conference aims at facilitating present and future collaborations in the field, and defining common research paths on stone inscriptions and inscribed landscapes.”

Below are my ruminations on this conference and the trips I made to museums in Paris on the following day.

First, here is some useful terminology.

| Sinographic: |

pertaining to the written form of the Chinese language. |

| Epigraphy: |

the study of (usually ancient) inscriptions.

(And, by extension, Epiverse: the physical and conceptual realm of inscriptions.) |

| Stele (pl. stelae): |

a (usually) stone monument bearing an inscription. |

15 October 2024

Digital Synergies

The digital “tools” (one of the speakers stressed that they should be regarded as “methodologies”) being used by historians to present information (metadata) about stelae in China in more useful forms. This was done by demonstrating the use of these methodologies in the speakers’ own investigations.

I, too, hope to develop (possibly simpler) “methodologies” by merging geographical, temporal, and other metadata to render the history of art (in particular, calligraphy) in a much more visual, immediate, accessible, and appealing form.

I have already discussed this project with a senior member of my university’s Art History department. I was offered some useful advice, but I still need to find someone who might be able to help with the coding aspect. I will make a prototype using VBA and a limited dataset while I continue to search for someone with whom I can collaborate.

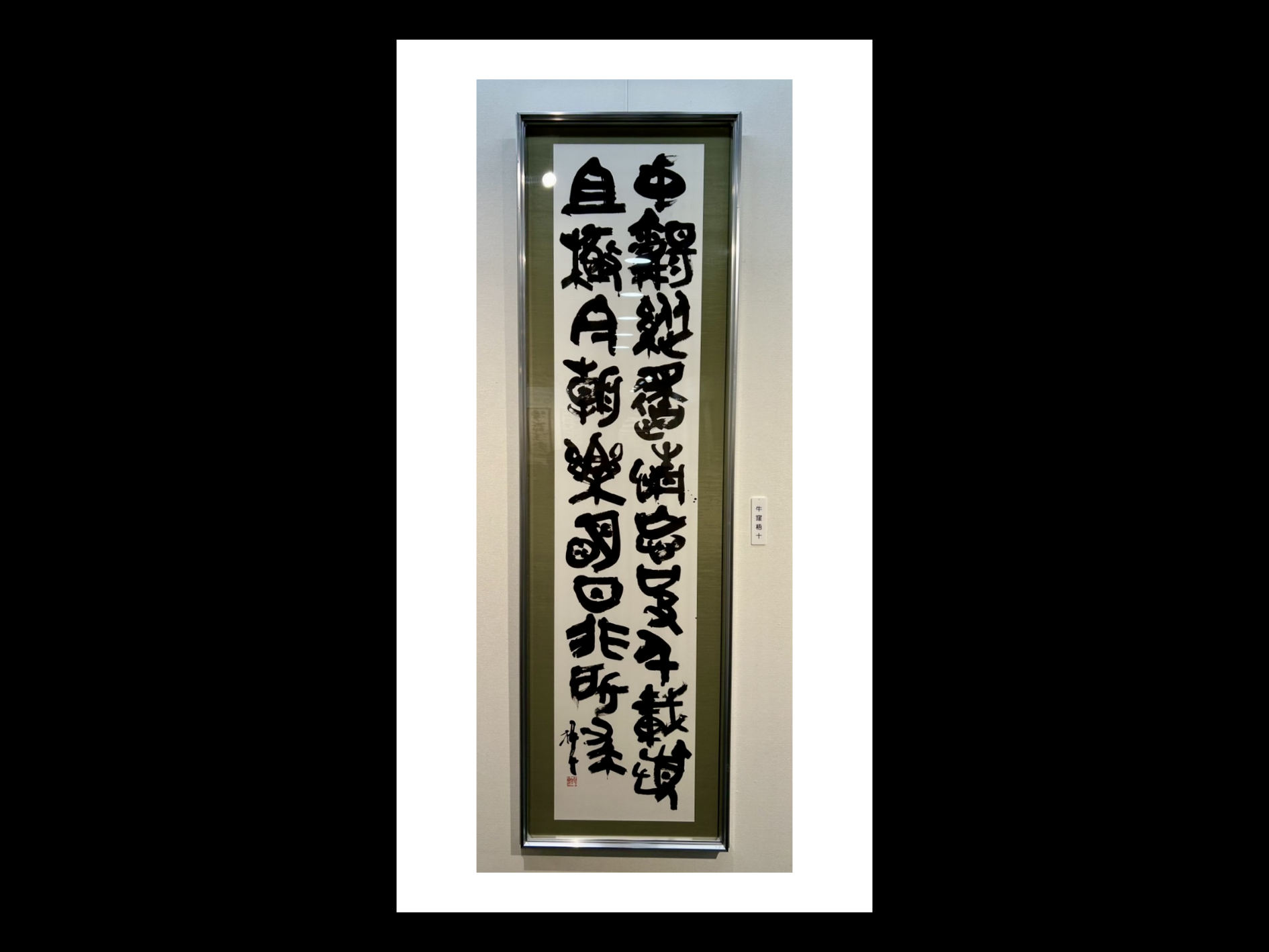

Calligraphic Variation

How can/should the various styles (seal, clerical (“chancery”), cursive (“grass”), running, and regular scripts) of Chinese calligraphy be defined? The speakers presented historical ideas about the characteristics of some of the styles. Often such descriptors are expressed in very lovely and poetic but vague language/imagery.

We also heard about the ways in which the writing styles of individual calligraphers (greats such as Ōgishi (Wang Xizhi, 王義之)) have been characterised.

Without such definitions, it would be impossible to talk about the variation observable in individual works (or parts of works) of calligraphy. These variations are not only inspirational for calligraphers but also helpful in determining cultural and social development and exchange in the past.

Much has already been written about calligraphic styles, and much more is yet to be written (including by myself).

As someone who has extensively observed, studied, and practiced all the major styles of calligraphy, I find that the distinctions between them are obvious; however, I have never vocalised many of the criteria which I apply in the classification process. I think that doing so (and doing so in conjunction with some form of quantitative visual analysis of the forms of characters) would be helpful.

One observation that I shared at the conference was that much of what I had read and heard (especially in English) about calligraphic styles was focussed on the static forms of kanji that appear on finished works of calligraphy (the spaces between strokes, the lengths and thicknesses of strokes, formal irregularities, etc.) rather than the strokes as a record of the movement of the calligrapher.

I commented that according to one Japanese treatise, calligraphy is more akin to dance than to any other art form (a theory that I already mentioned in the Jazzigraphy blog post), and that maybe the systems of stylistic classification in dance could help inform the debate about stylistic classification in calligraphy.

I would have liked to go on to mention that–just as in dance–rhythm and attitude are essential differences between calligraphic styles.

In my own experience of writing calligraphy, switching styles without taking a decent mental break invariably leads to disappointing results. I would not recommend writing more than one style per day to any student of calligraphy, especially to one in the intermediate stages of their learning. It is a testament to a calligrapher’s skill if he/she is able to switch styles and continue to write well.

Traveling Legacy

Not such an illuminating presentation/discussion, other than to confirm that although some excellent pieces of calligraphy have been produced in Korea, there are several reasons why Korean calligraphy largely passes under the radar (certainly in Japan): the disappearance of kanji from much of daily life and the paucity of calligraphic research to name but two.

Transforming Spaces

Again, an interesting topic (in what locations are ancient stelae found and what information is contained in the text of their inscriptions), but this was geared more towards the social historians in the audience.

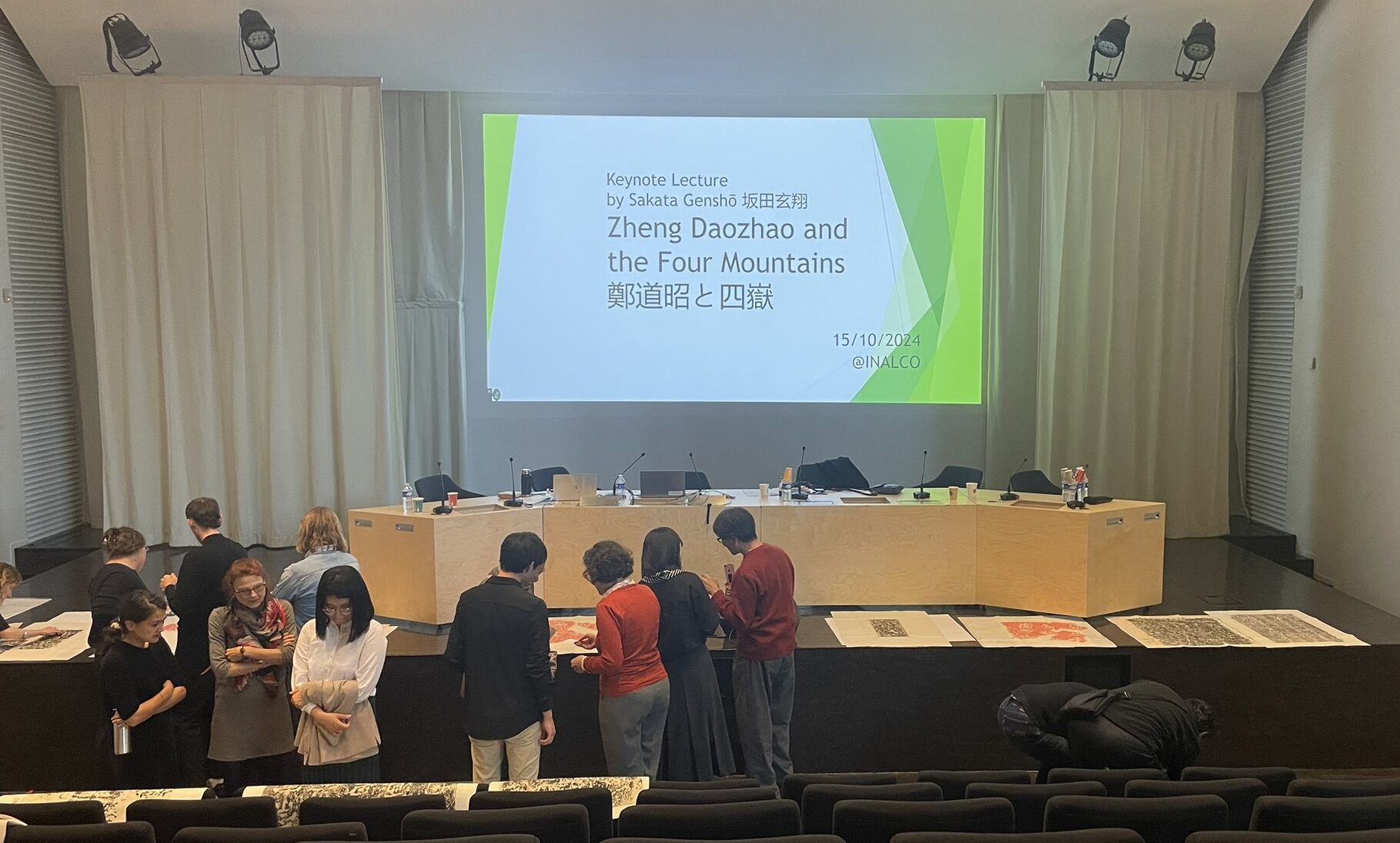

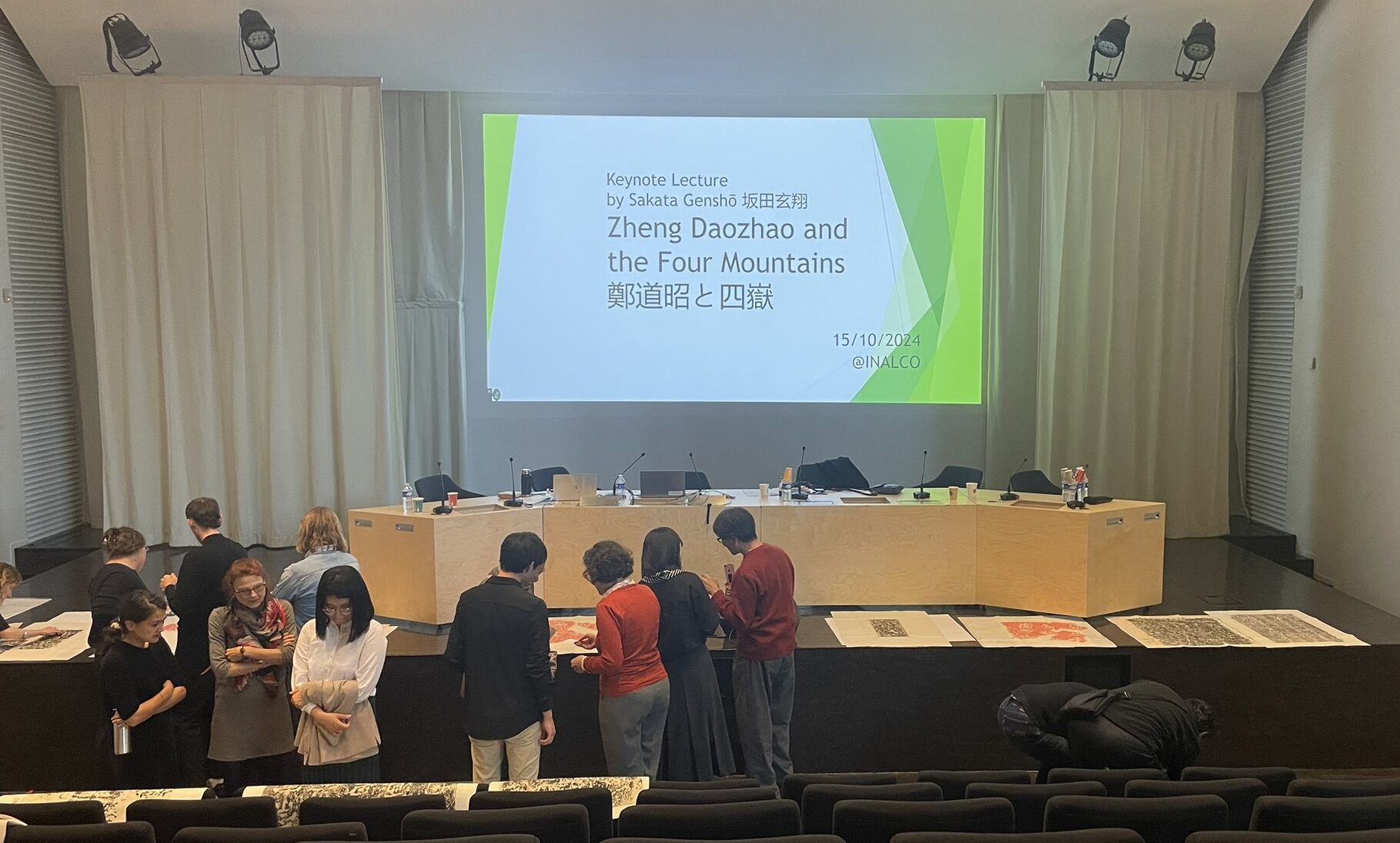

Zheng Daozhao and the Four Mountains

Attendees inspect a tiny fraction of Sakata-sensei’s vast collection of rubbings.

It was a real treat to listen to and have the chance to chat with Sakata Genshō (坂田玄翔): an inspirational independent scholar and field archaeologist.

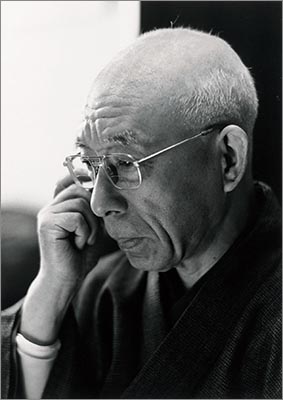

I was starstruck to hear that he had been personally acquainted with one of my heroes, the modern Japanese tenkoku-ka (篆刻家, seal carver) Kobayashi Tōan (小林斗盦, 1916 – 2007). Moreover, Sakata-sensei mentioned that he had had some seals carved for him by the great man himself.

Kobayashi Tōan (小林斗盦, 1916 – 2007).

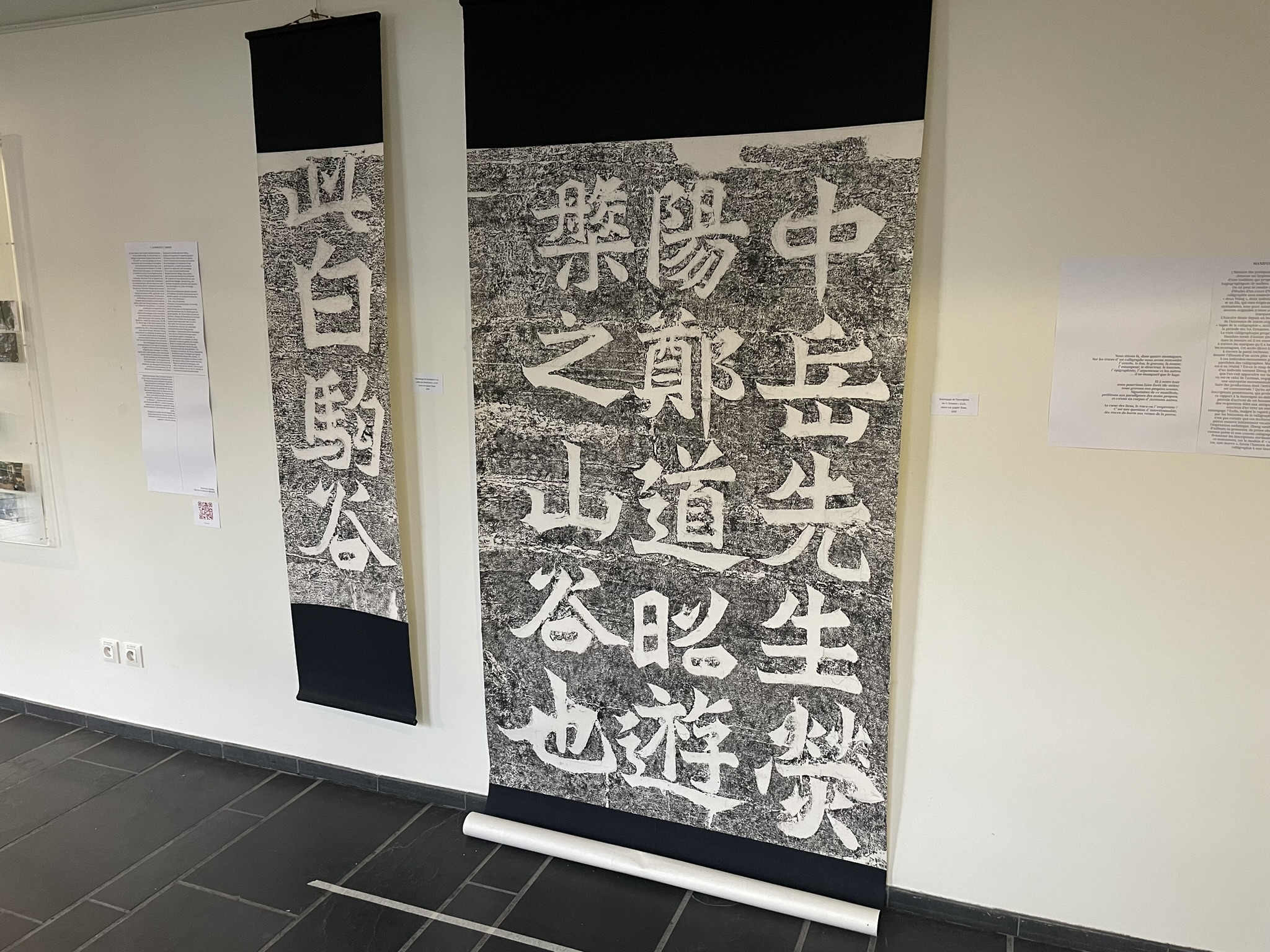

Sakata-sensei’s obsession with the inscriptions (sometimes falsely) attributed to Zheng Daozhao (鄭道昭, JP: Tei Dōshō, ? – 516 CE) stems from his discovery that these inscriptions constitute a kind of portal to the world of a Taoist scholar who lived about 1,500 years ago. Unlike many contemporaneous inscriptions, they contain personal details which Sakata-sensei has used to piece together the life of a man who may have communed with immortals…

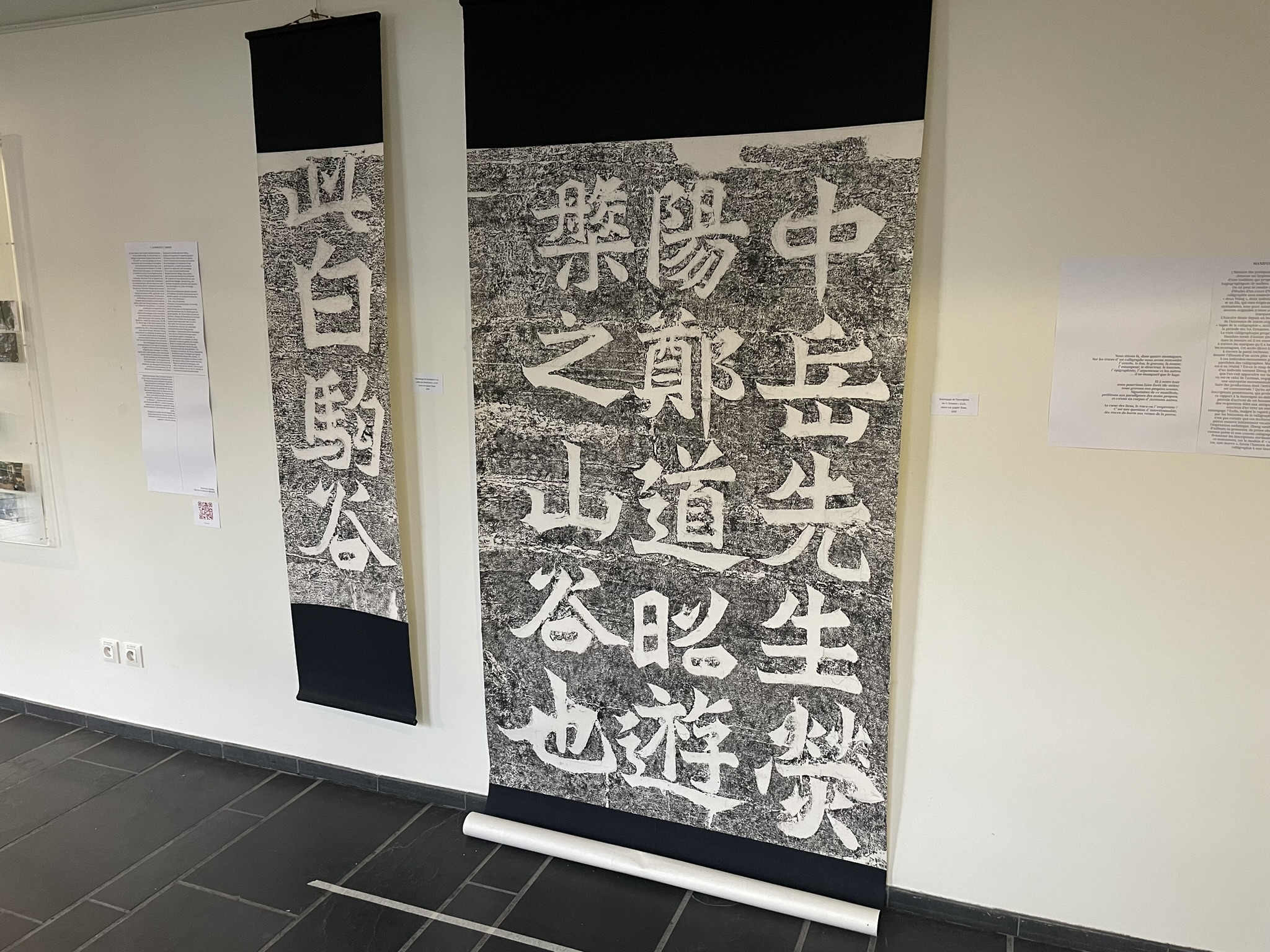

Rubbing of an inscription that refers to Zheng Daozhao (鄭道昭).

Personally speaking, although the inscriptions attributed to Zheng Daozhao are accomplished pieces of calligraphy, they do not contain as much eccentricity or refinement as other inscriptions from the Northern Wei dynasty, such as Sonshūzōzōki (孫秋生造像記) or Chōmōryōhi (張猛龍碑), and are consequently of less interest to calligraphers.

16 October 2024

Thinking Matters

Fascinating presentations from two very engaging speakers that–despite both focussing on Taoist monuments–brought opposite applications of their extensive research. The first focussed on using inscriptions to trace the course of Taoist thought through time and gauge the influence such thought had in wider society; the second focussed on the challenges faced in trying to protect inscriptions so that they may be experienced and studied for many years to come.

One takeaway for myself from the second presentation was the geological aspect of epigraphy: how does the type of rock into which an inscription is carved determine the forms of characters which we see in the present day? This is something I would like to explore a little further, even though it might end up being of little consequence from a calligraphic perspective.

It was also interesting to learn that Chinese commentaries on geology were being written as long ago as the Song dynasty (960 – 1279 CE) and that Chinese scholars had begun to guess at the scale of geological time long before European scientists had made their own remarkable breakthroughs regarding the cooling of the earth and plate tectonics.

Conceiving Identity

An extension of earlier sessions on how we can learn about individuals (particularly Zheng Daozhao) from inscriptions.

Many stelae have been moved from their original locations (for reasons of convenience of viewing, protection, etc.), and this loss of context complicates the process of deciphering the information contained within such records. Moreover, “new” stelae are being discovered all the time, and such discoveries can radically alter interpretations of hithertofore “well-known” stelae.

View of the skyline from INALCO.

Screening of Arpenter un paysage inscrit

The film of the INALCO team’s recent trip to China to document the inscriptions on Tianzhushan and Dajishan was superb: one of the highlights of the conference for me. Even though the film is not yet finished, it captured the locations and the team’s fieldwork beautifully. There was also a demonstration of a jaw-droppingly detailed 3D computer model of Tianzhushan.

I could not help being struck by the weather–in particular the wind–shown in the film. It has blasted the inscriptions on these mountains for fifteen centuries. I asked whether it might not be possible to use the technology that is now available, together with the expert knowledge of meteorologists and geologists and the physical data collected by the INALCO team, in order to virtually restore the inscriptions to their pristine state. Older rubbings of the inscriptions (noting, however, Sakata-sensei’s caveat on the inaccuracies of these) could also inform this project. Careful consideration, though, should first be given to the likely benefits resulting from what would be a considerable expenditure of time, effort, and money.

Managing Monuments

Continuing the theme introduced earlier, the two speakers described what is being done to protect Chinese stelae from weather, theft, vandalism, and (possibly most urgently) rapidly increased domestic tourism due to China’s recent economic development. Ironically and lamentably, some protection efforts themselves are damaging the stelae.

The general consensus among attendees at the conference seemed to be that stelae should not be restored. They should be allowed to age naturally and with dignity. I wholeheartedly concur: the weathering of stelae adds to the range of expressive possibilities already contained in the forms of the characters in the inscriptions.

Antiquarian Practices

An excellent joint presentation about the differences between directly experiencing stelae and indirectly experiencing them through rubbings, drawings/paintings, photographs, etc. (I wish I could have paid much more attention to this presentation, but I was flagging somewhat by this point in the proceedings… )

It can often be inconvenient, difficult, or even impossible to directly access stelae, and the greater part of the scholarly canon about stone inscriptions is based on secondhand experiences (“armchair archaeology”).

However, I believe that one can argue that records of stelae often add new elements to the sensory experience. For historians trying to accurately depict the past, these new elements are often distracting (they can occasionally be informative). From the perspective of art appreciation, though, the records of stelae are sometimes even more charming than the stelae themselves.

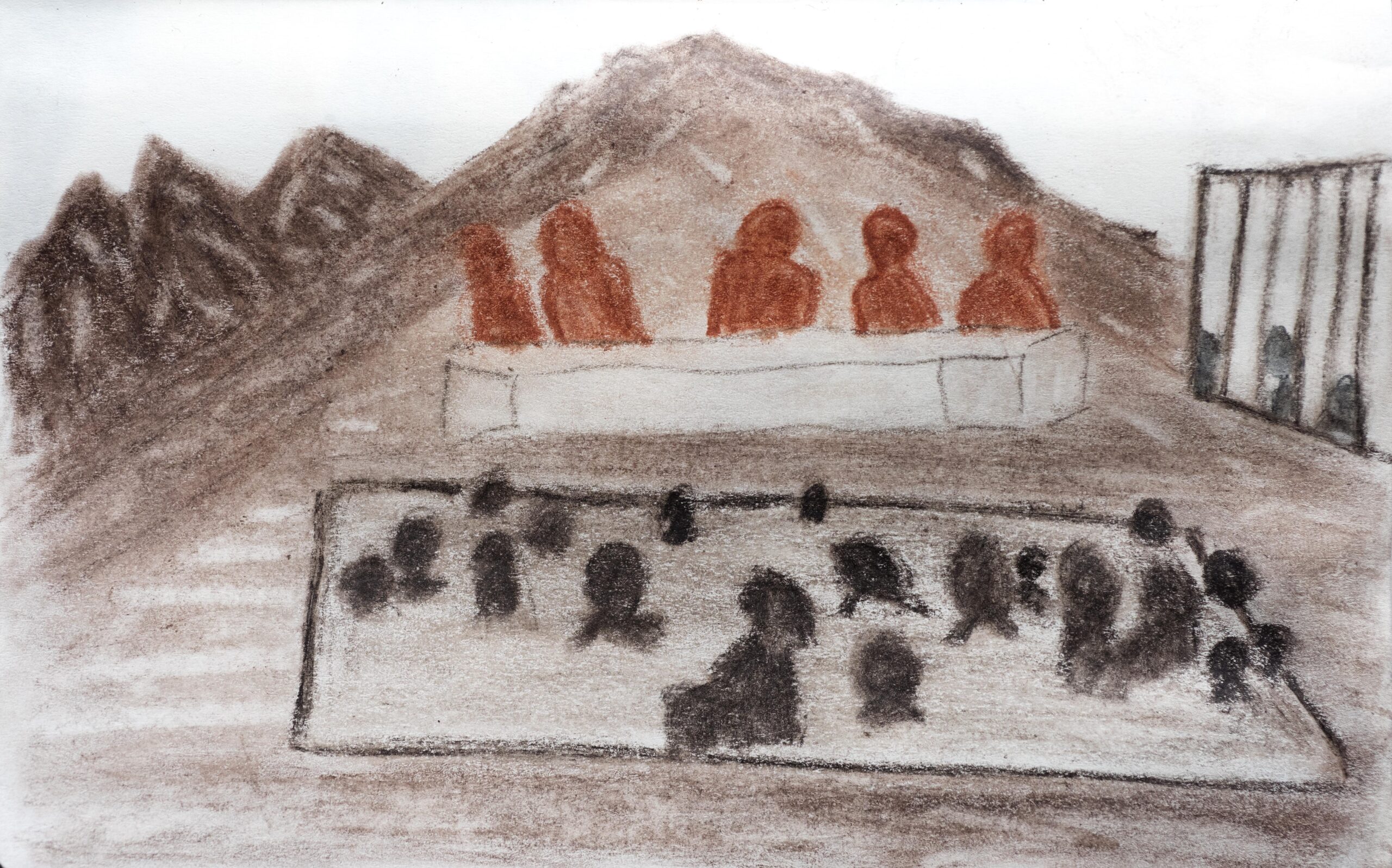

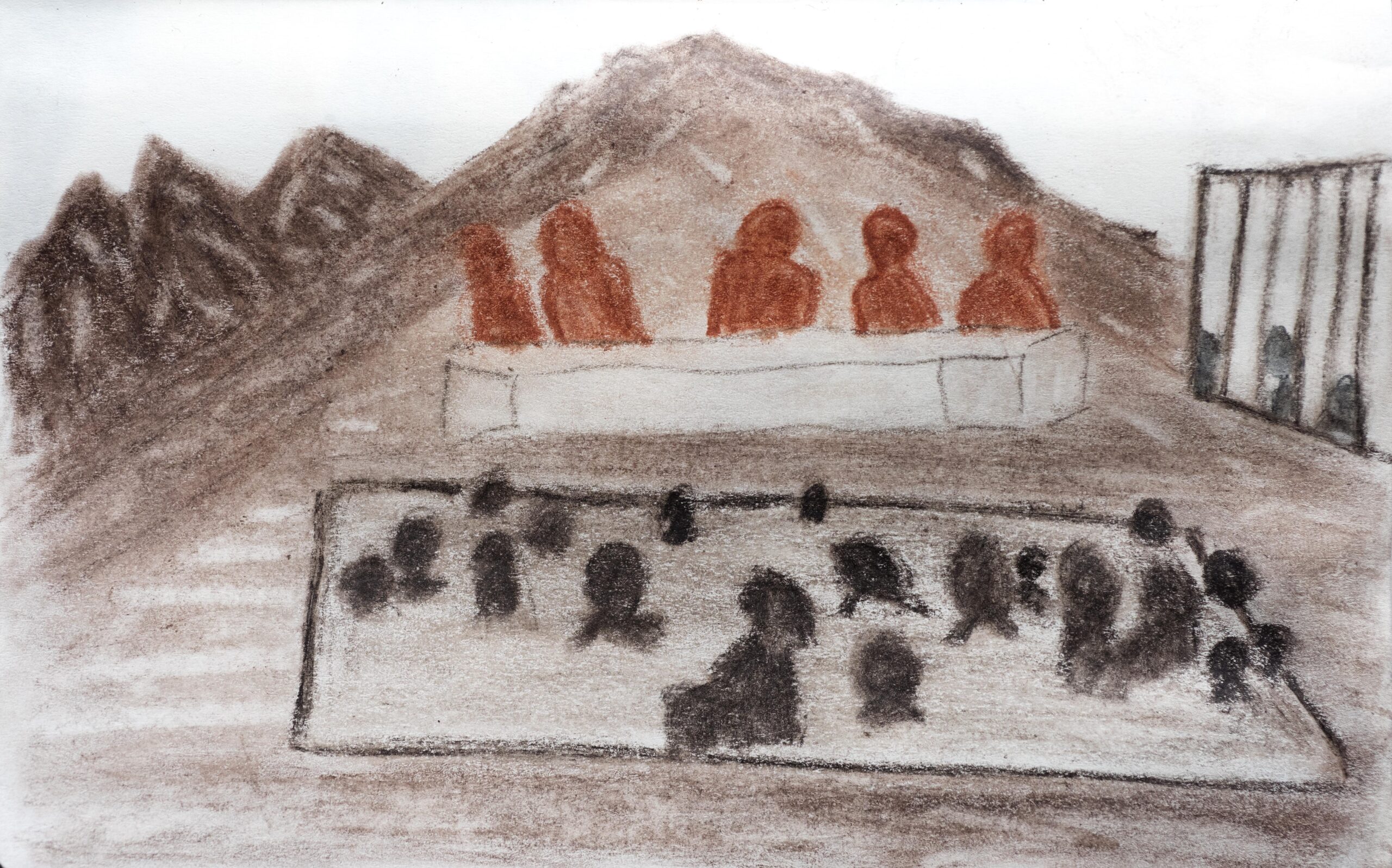

© 2024 Marie-Françoise Plissart.

This lovely drawing of the conference was executed by one of the participants. I like the inclusion of the window on the right and the curious passers-by looking in.

The welcoming atmosphere of the conference and the opportunities to discuss fascinating topics with experts were thoroughly enjoyable. I hope that I will be allowed to attend and even present at similar conferences in the not-too-distant future.

17 October 2024

On the rainy day following the conference, I visited the Musée Cernuschi and the Musée Guimet.

The Cernuschi’s collection is small but of exceptionally high quality, reminiscent of the Nezu Museum in Tokyo. The Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE) bronze vessels and the incense burners from Edo-period Japan (1603 – 1868 CE) were particularly wonderful. Unfortunately, photography was not allowed inside the museum.

Musée Cernuschi.

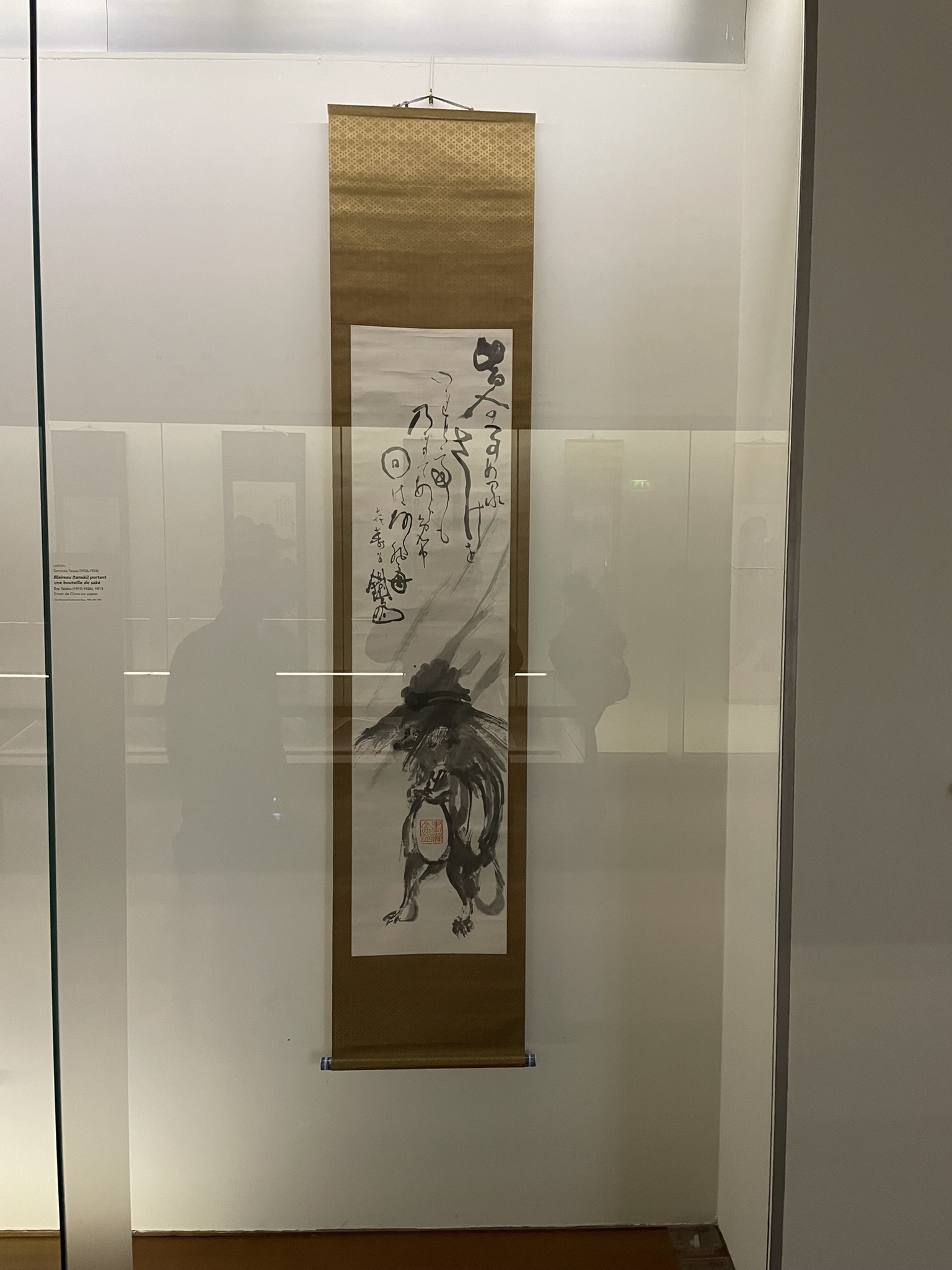

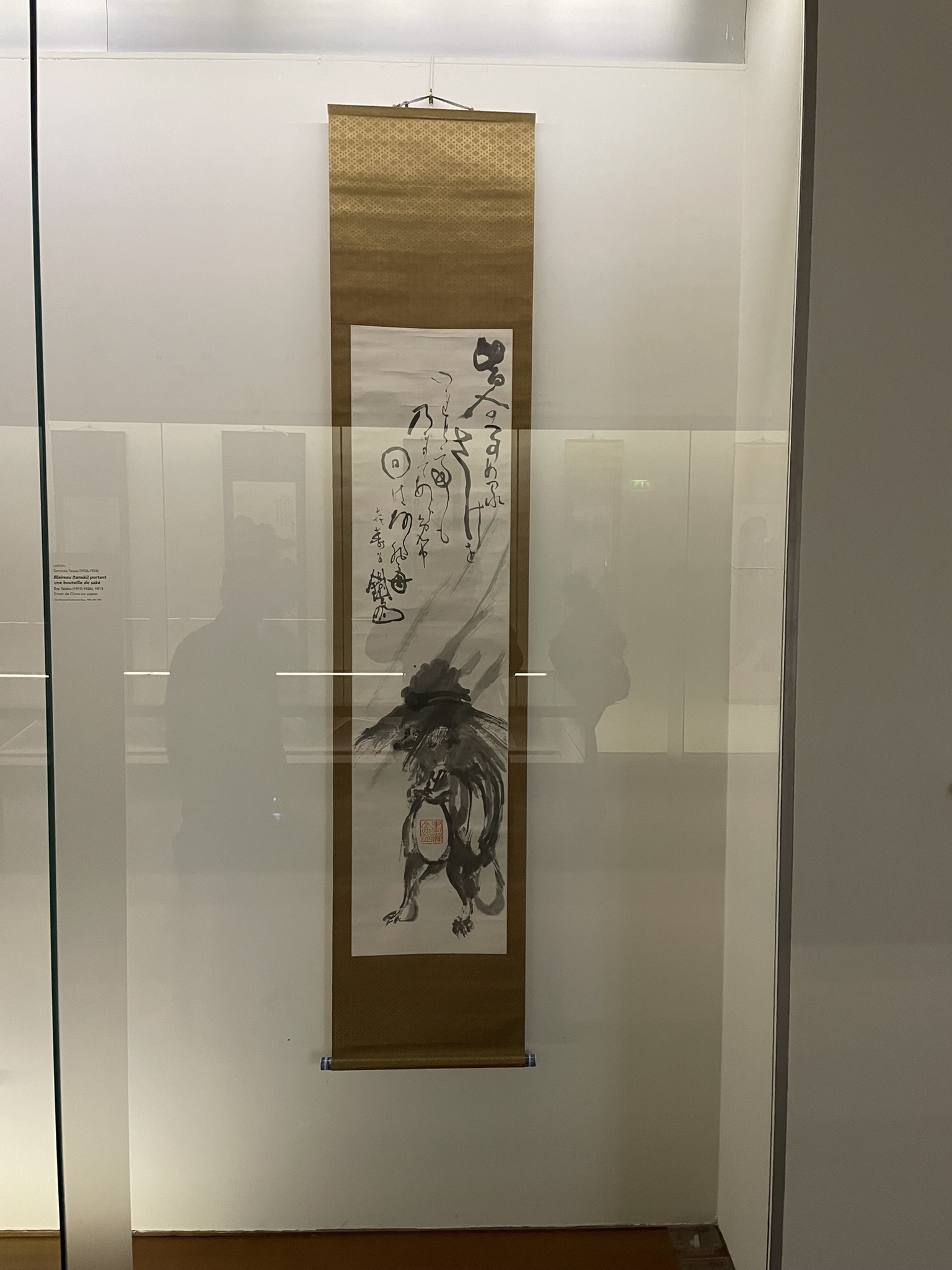

The Musée Guimet has a stunning collection. Moreover, it currently has an exhibition of ink paintings and calligraphy by Tomioka Tessai (富岡鉄斎, 1837 – 1924 CE)–not a personal favourite, but an important figure in the modernisation of Japanese calligraphy.

Exterior of the Musée Guimet.

Part of a delightful exhibition of contemporary works inspired by Shang- and Zhou-dynasty bronzes.

A painting by Tomioka Tessai of a badger holding a large jar of saké.

Statue of a lion.

Khmer art.

After seeing these, I had Bring Me Sunshine in my head.

In all seriousness, there were an awful lot of stone bodies without heads and stone heads without bodies. There were even huge sections of wall that had been transplanted to Paris so that well-fed Europeans could marvel at the sophistication of ancient Asian cultures.

The odour of colonialism was overpowering. The museum had taken pains to point out that many of the exhibits had been donated by wealthy Asian collectors, but I cannot help but feel that with the technology we now have (or could soon develop if the will was there), many of these artifacts could be returned to and enrich (both culturally and economically) the places where they were made.

– Matthew (真秀, Mashū)