An Introduction to the Japanese Language

To better understand how the Japanese language works, it helps to have some idea of how it evolved…

An early example of written Japanese.

Kanji in Japanese

Until about 1,500 years ago, there was no system for writing Japanese. It was a purely spoken language called wago (倭語 or 和語). However, that changed following the arrival of Buddhism in Japan.

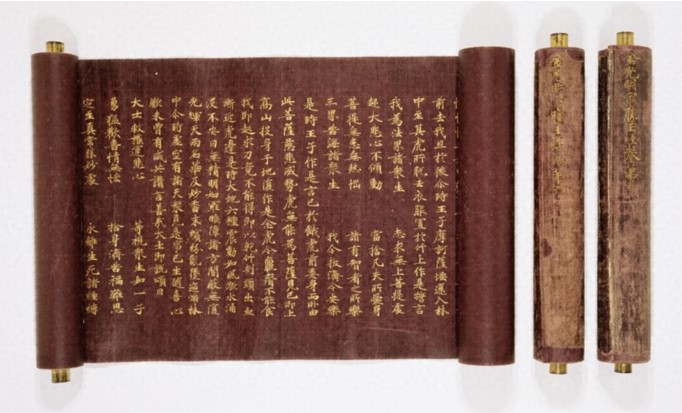

Buddhism had become immensely popular in China after its introduction from India via the Silk Road trade routes. Buddhist sutras and other teachings were translated into Chinese – a language which already had a sophisticated writing system – and the practice of copying sutras as a form of meditation or prayer developed.

A handwritten Buddhist sutra from the 8th century.

The popularity and practices of Buddhism spread southwards, through the Korean peninsula and into Japan, where it was warmly received by members of the Japanese aristocracy, whose resources and influence allowed the new religion to quickly take hold.

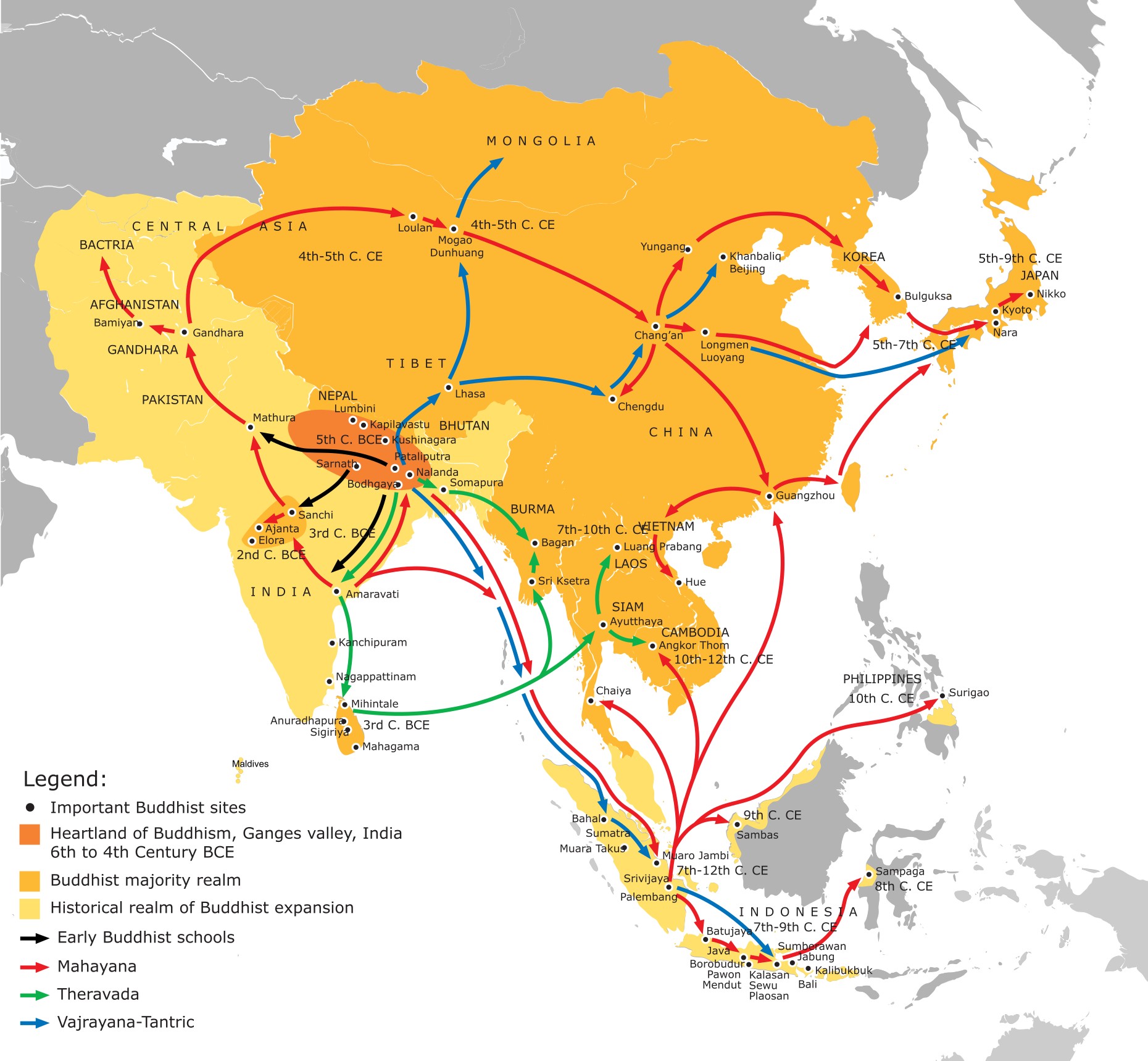

The spread of Buddhism in Asia

by Gunawan Kartapranata, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link.

Click to zoom.

Before long, the Japanese realised that they could use the Chinese characters in Buddhist scriptures to write their own language. Each character (called hanzi in Mandarin Chinese and kanji in Japanese) represented an idea, and many of those ideas were represented by sounds in wago, so the existing Japanese sounds were linked to their corresponding kanji.

For example, the sound ki is used in Japanese to represent the idea of “tree” and the kanji 木 also represents the idea of “tree,” so ki became linked to 木.

At the same time, each kanji was already linked to a sound in the Chinese language. In the example above, 木 was linked to the sound mu in Chinese. These Chinese sounds—well, “Japanized” versions of these sounds—were imported along with kanji. So, 木, for example, was also linked to the Japanized Chinese sound moku.

(Scholars are, of course, uncertain what these sounds would have actually been 1,500 years ago.)

As a consequence, many kanji have a Japanese sound—known as a kanji’s kun reading—and a Japanized Chinese sound—known as a kanji’s on reading—linked to them.

Here is a table of common kanji with their associated kun and on readings, as well as their associated sounds in contemporary Mandarin Chinese.

| Kanji: | 木 | 土 | 水 | 火 |

| Meaning: | tree | earth | water | fire |

| kun reading: | ki | tsu·chi | mi·zu | hi |

| on reading: | mo·ku | do | su·i | ka |

| Mandarin: | mu | tu | shui | huo |

One of the consequences of using kanji was that not only Buddhist scriptures but also other forms of Chinese literature, including poetry and Taoist and Confucian writings, became accessible to educated Japanese. Even today, with some additional study of classical Chinese grammar, people who can read and understand Japanese can also read and understand classical Chinese, and studying Chinese texts is part of the curriculum in many Japanese schools.

Chinese literature introduced many words and phrases of two or more kanji to the Japanese language. As a result, many—although not all—Japanese words that are comprised of two or more kanji are read using their kanji’s on readings.

By contrast, when kanji are used individually in Japanese, they are often—but not always—read using their kun readings.

For example:

| Japanese: | 私 | は | 学生 | です。 |

| Hiragana: | わたし | は | がくせい | です。 |

| Romaji: | wa·ta·shi | wa | ga·ku·se·i | de·su。 |

| Readings: | kun | on | ||

| English: | I | student | be | |

| Translation: | I am a student. | |||

There are some phrases that use only kun readings, such as 見事・みごと・mi·go·to = “splendid.”

There are some that use a combination of on and kun readings, such as 重箱・じゅうばこ・jū·ba·ko = “stackable lunchbox.”

There are also some kanji that do not have kun readings, such as 感・かん・ka·n = “feeling, emotion.” (Maybe these ideas did not exist or were expressed indirectly in wago.)

As a result, the observation above about the readings of kanji when used individually or in phrases is absolutely not a hard-and-fast rule.

Hiragana and Katakana Syllabaries

The introduction of kanji to Japan had a profound influence on Japanese culture. The Japanese clearly enjoyed writing, and The Tale of Genji written by Murasaki Shikibu in the early 11th century is regarded by many as world’s first full-length novel.

Kanji, though, could not capture all the aspects of wago. For example, verbs are conjugated (their endings are changed) in Japanese to indicate when the action took place or to show respect. By contrast, verbs are not conjugated in Chinese.

To fill this gap, the Japanese created two phonetic syllabaries: two sets of characters which are associated with sounds but have no meanings (like the characters of the alphabet).

One set was developed by using cursive forms of kanji with the same or similar sounds. This set is called hiragana (平仮名・ひらがな = “plain borrowed name”). Because of their cursive origins, the strokes used to write hiragana characters are usually curved and written fluidly.

| Kanji | on reading | Cursive form | Hiragana |

| 以 | i |  |

い |

The other set was developed by using a few of the strokes from kanji with the same or similar sounds. This set is called katakana (片仮名・かたかな = “fragmentary borrowed name”). These were extracted from the forms of kanji in regular script, so the strokes used to write katakana are usually straight and written one at a time.

| Kanji | on reading | Extracted strokes | Katakana |

| 伊 | i |  |

イ |

Both hiragana and katakana are comprised of 46 characters, and there is a one-to-one correspondence between the two sets. There are five vowel characters, 40 characters that are a combination of a consonant plus one of the five vowels, and the character for the sound /n/.

These days, hiragana and katakana characters are usually organized into charts according to their initial consonants, and you can see a examples of a hiragana chart and a katakana chart on this website (links open in a new window).

Traditionally, the hiragana and katakana characters were organized and memorized using the following special poem. It was composed to contain each character exactly once, although it contains two characters that are no longer in common usage: ゐ (wi) and ゑ (we).

| Hiragana: | いろはにほへと ちりぬるを わかよたれそ つねならむ うゐのおくやま けふこえて あさきゆめみし ゑひもせす |

| Romaji: | i·ro wa ni·o·e·do chi·ri·nu·ru o。 wa·ga yo ta·re zo tsu·ne na·ra·mu。 u·i no o·ku·ya·ma kyō ko·e·te、 a·sa·ki yu·me mi·ji e·i mo se·zu。 |

| Translation: | “All colors are fragrant, but they soon scatter. Who in our world can remain forever? Today I will cross the deep mountains of existence, And I shall not indulge in shallow dreams nor be intoxicated.” |

Modified characters and compound characters

In addition to the 46 basic characters, the consonant sounds of some characters can be modified by adding two small dots to the top right-hand corner of the character. These dots are known as dakuten (濁点・だくてん = “muddy mark”). Adding dakuten to the character for ta, for example, changes it to da.

The consonant sounds of five of the characters can also be modified by adding a small circle to the top right-hand corner of the character. This circle is known as handakuten (半濁点・はんだくてん = “half-muddy mark”). Adding handakuten to the character for ha, for example, changes it to pa.

Some pairs of characters can be joined to make new sounds. For example, we can join the characters for ki and ya to produce the sound kya. When we write these sounds, the second character is written about half the size of normal characters, so kya would be written as きゃ using hiragana and キャ using katakana.

Learning Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji

Thankfully, you don’t need to master kanji, hiragana, and katakana before learning Japanese.

The sounds of the Japanese language can be written using the characters of the Roman alphabet (a, b, c, d, … ). This way of writing Japanese sounds is called ローマ字・ろーまじ・rō·ma·ji = “Roman letters.”

Romaji is a great way for beginners to start learning Japanese words and grammar.

At the same time, there are a few potential pitfalls one should be aware of when using romaji:

- The pronunciations of some consonant sounds—particularly hi, fu, ra, ri, ru, re, ro—are somewhat different to how native English speakers are taught to pronounce them.

- When rendered in romaji, some Japanese sounds have one character, some have two characters, and some have three. In hiragana and katakana, each Japanese sound has one character and is vocalized for the same length of time.

- Native English speakers have a tendency to use the rules of English pronunciation when pronouncing Japanese words written in romaji. For example, adding stress to syllables or blending sounds.

- There are a number of different systems for writing romaji, and the differences between them can confuse learners. For example, the word 紅葉・こうよう・kō·yō = “red (autumn) leaves” can be written in romaji as kōyō, kouyou, koyo, or kohyoh depending on the system being used.

Romaji is very useful, but I strongly recommend learning hiragana as soon as possible. It will really help your pronunciation and it helps when learning the rules of Japanese grammar.

Once you are reasonably confident with hiragana, move on to katakana. Don’t try to learn both at the same time!

In order to help students learn hiragana and katakana, I have created some hiragana & katakana flashcards (opens in a new window). There are listening and spelling quizzes to help reinforce what you have learned and allow you to gauge your progress.

When it comes to kanji, I personally believe that it is better to learn kanji as you come across them in Japanese texts, rather than studying lists of individual kanji. (That said, studying lists is not ineffective, and I am presently devising flashcards for kanji self-study.) So, I recommend looking for simplified Japanese texts in which the readings of the kanji are printed next to them (known as furigana).

In preparation for the JLPT N2 and N1 tests, I read the entire Harry Potter series in Japanese. Knowing how the stories developed helped me to follow the text, and as they are great stories and have been superbly translated into Japanese, it was a very enjoyable way to study. Moreover, as the books were targeted at children in Japan, they had furigana. (Books written for adults usually only have furigana for rare kanji.)

Kanji can be daunting. As well as having to remember the complex shapes, stroke orders, and meanings of kanji, as we saw above, kanji often have at least two ways of being read with little or no connection between the readings. (Some kanji have more than two ways of being read… )

Remember this: Kanji are made up of simpler elements, some of which are kanji themselves. If your familiarise yourself with these elements, you’ll find that kanji are not quite as difficult as they seemed at first. Moreover, the simpler elements which comprise a kanji contain clues about its meaning and its on reading.

The comparatively small number of sounds in the Japanese combined with the rich history of the language entail that Japanese contains many homonyms: words with the same pronunciation but different meanings. If you understand kanji, you will quickly be able to understand which meaning is intended by a speaker. In fact, you will start to “see” kanji in your head as you hear them. And that is pretty cool!