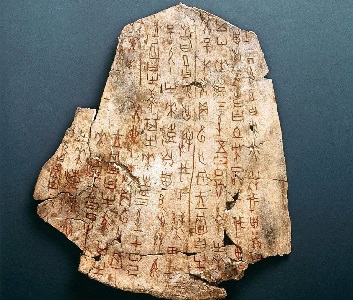

The material on which calligraphy is written has changed throughout its history. The oldest surviving calligraphy was scratched into cattle bones and turtle shells. Later, it was written with a brush on a piece of leather, a knife was used to cut out the lines that made up each character, and the piece of leather was then pressed into the soft clay used to make the mould for a bronze vessel.

Kanji carved into bone.

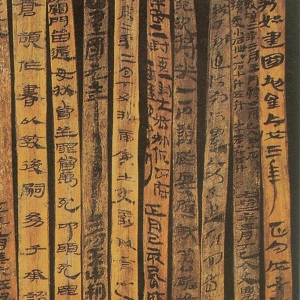

The next advance was to write with a brush onto thin strips of wood or bamboo, which were tied together with string to make books.

Brush-written characters written on strips of wood called mokkan (木簡).

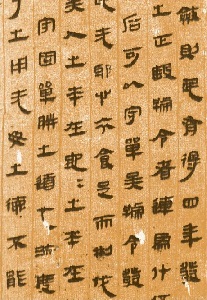

China is famous as the birthplace of silk, and writing on silk was found to give more pleasing results than writing on wood or bamboo. What is more, very large sheets of silk could be produced. This had quite a profound effect on calligraphy because it allowed calligraphers to write characters larger. This, in turn, allowed them to devote more attention to the form and expression of individual lines. Silk has been used for many hundreds of years in China and Japan for both calligraphy and painting.

Calligraphy written on silk, known as hakusho (帛書).

However, it is expensive to use silk. During the later Han Dynasty, paper production techniques had advanced to the point where it became cheaper than silk, and since that time, paper has been the principal material on which calligraphers write. It is strong but light, and it can be made from a variety of different plant fibres, giving it different properties and appearances.

Making paper

Paper is made by evenly mixing pulped plant material with water-based glue and water. The mixture is then spread out thinly over a screen and allowed to dry (screening). The type of plant material and the screening method affect the quality of the paper that is produced.

Screening can be done either by machine or by hand. It goes without saying that machine-screened paper is much cheaper to produce than hand-screened paper.

Machine screening can be further subdivided as follows.

Maruami-screened (円網抄き, maruami-suki) paper

The pulp used for this method is from broad-leaved trees. The mixture is poured over a rotating cylindrical mesh. The water drains into the centre of the cylinder, and the pulp and glue mixture is left on the mesh. This is then lifted onto a bed of felt and passed through rollers and dryers to remove any remaining water.

The difference between the two sides of the paper produced by this technique is obvious. The “front” is very smooth, whilst the “reverse” is rough. When writing with ink on the “front” of this type of paper, there is very little bleeding (滲み, nijimi) and dry brush strokes (擦れ, kasure) are hard to produce. The wet ink remains on the surface of this kind of paper, and if not given plenty of time to dry, it will drip when picked up.

Tanmō-screened (短網抄き, tanmō-suki) paper

For this technique, the mixture is poured onto a flat mesh. The advantage of this technique over maruami screening is that pulp from straw, hemp, mulberry, bamboo, mitsumata (known in English as the Oriental paper bush) and ganpi (Diplomorpha sikokiana) can be used. These are the raw materials from which Japanese paper (和紙, washi) and Chinese paper (唐紙, tōshi) are traditionally made. They give the paper additional strength, allowing it to be made thinner, as well as having a more pleasing appearance.

Although paper made using this technique is similar in appearance to handmade paper and better-quality than maruami-screened paper, it does not allow the range of expression that handmade paper does.

The video below shows both the maruami– and tanmō-screening methods at the Marujū Paper Company’s factory.

Handmade (手漉き, te-suki) paper

This paper is made by dipping wooden frames covered with a fine mesh into a bath of the pulp, glue, and water mixture. There can be slight inconsistencies in the thickness and quality on a single sheet, but this is the best type to use for calligraphy because it bleeds well, allows dry brush strokes to be produced easily, and gives depth to brush strokes.

Handmade paper is used not just for calligraphy but also for a variety of purposes, including the paper used on traditional Japanese sliding doors (障子, shouji). The video below demonstrates the level of care and craftsmanship that goes into handmaking paper.

Processed paper (加工紙, kakōshi)

Calligraphy paper can also be dyed, printed with patterns, or even have pieces of metal foil stuck onto its surface. Although such paper is beautiful, it tends to be expensive, so it is best to use it only for exhibition pieces and not for your everyday practice.

Kakōshi with metal foil.

Choosing paper

Choosing which kind of paper to use is, like many things, a trade-off between price and quality. The quality of paper differs widely. You could use cheap maruami-screened paper for your everyday practice and handmade paper for exhibition pieces. However, it might be challenging (i.e., take many sheets) to get used to a different kind of paper, especially if there is a big difference in quality. The best advice would be to use the best-quality paper that you can afford for your everyday practice, so that you are ready to write on better-quality paper for your exhibition pieces.

Your choice of Japanese paper (和紙, washi) or Chinese paper (唐紙, tōshi) will also depend on the style of calligraphy that you write. Washi is best for writing kana (Japanese cursive script). Writing kana involves producing crisp, thin lines using hand-rubbed ink, and washi is not so absorbent, meaning that it does not bleed very much. Moreover, the ink tends to retain its colour. Tōshi, which is usually made from pulped bamboo, is much better at sucking up ink, allowing bleeding and dry brush strokes, making it the paper of choice for calligraphers wishing to write kanji expressively.

Among the different kinds of tōshi, the best is reckoned to be senshi (宣紙). Although this was originally exclusively produced in the Anhui province of eastern China using cedar and rice straw, it is now made in numerous locations using a variety of raw materials.

Senshi is available in a variety of thicknesses.

- Tansen (単宣): This is the standard thickness for senshi.

- Kyōsen (夾宣): To make this thicker paper, twice as much of the pulp, glue, and water mixture is loaded onto the screen.

- Nisō-kyōsen (二層夾宣): This very thick paper is made from two layers of the thick kyōsen paper.

The thicker the paper, the more ink it will suck up: thinner paper will bleed outwards, whilst thicker paper will bleed downwards. This means that if you want to use lots of ink and produce very strong-looking lines, your best bet is to use kyōsen or nisō-kyōsen. If you prefer to have more bleeding and write more delicately, tansen is for you.

Whichever type of paper you choose, be aware that each sheet will have a “front” side and a “reverse” side. The “front” will be smoother than the “reverse,” although sometimes it can be hard to tell the difference between the two. One simple technique that can help you is to run the tip of your finger over the two sides of the paper. The side that feels cooler is the “front.”

The “front” is the side which should be written on. Writing on the rougher “reverse” side will not produce such pleasing results, and it will not be as pleasant to write on, as the additional friction will not allow the brush to move smoothly over the surface of the paper.

Paper should be stored out of direct sunlight and in a place where there is good ventilation. Ideally, use a paulownia wood box to store your best paper, but if this is not possible, wrap it in thick paper.

It takes 2 to 3 years for the glue used in making paper to dry completely, and for this reason, many experienced calligraphers will keep a stock of their favourite paper. It is said that paper stored properly for over 10 years is the best to use: the ink will go on well and its colour will be exceptional, bleeding will be easy to control, and dry brush strokes will be beautiful.